During my first journey with the Johns Hopkins psychedelic study I was part of, I received a message. Not by words so much as a thought form which I translated into words. The message was:

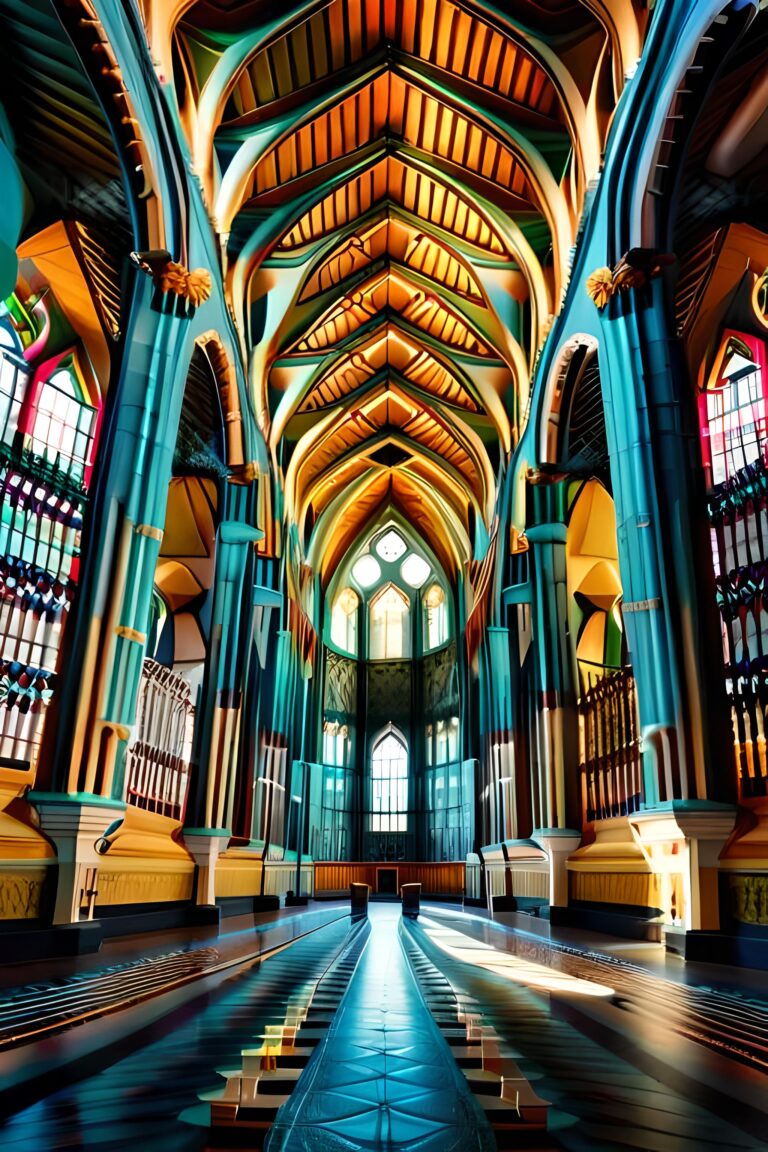

Beauty is leaving the earth. You must become a curator of beauty so that those who come after you will remember the beautiful.

The message is profoundly troubling, dark, and deeply tragic. I came away understanding I was shown beautiful things in my experience in order for the message to be delivered, and one would suppose, to be acted upon in some way.

Wrapped up in the message is a begged question, or one of many I suppose. The begged question is, “What is beauty, and what does it mean to say something is beautiful?”

Before we get into that, let me say that these sorts of questions are part of the second aspect of an Extraordinary Spiritual Experience (ESE), which is Appearance. (In this post, I am working from the future and speaking in terms of the kinds of ideas we might use to integrate an ESE.) What I mean by ‘Appearance’ is quite simply ‘whatever or whoever is showing up in an ESE’. What is showing up could be an idea, a landscape – a ‘where’ (which would lay the foundation for a new Set and Setting); an entity such as an angel, a god, a demon, a person living or dead – a ‘who’; an abstract shape or form, a feeling, or a mental state – a new ‘set’, perhaps; or any one of many other wheres and whats and whos.

An excellent example of the Appearance aspect of an ESE is in the story of Abram in the first book of the Bible, Genesis. There, Abram is living with his wife, Sarai, in Mamre. They are very old at this point in the story. Note the Set and Setting here – we have a place, a Setting, likely a desert oasis, and we have a Set – Abram and Sarai are old and on their own.

The Appearance happens when three angels, or messengers, or sometimes ‘watchers’ depending on the translation, show up on a hill by Abram’s home in Mamre. Abram does not yet perceive these beings as angels. Instead, he perceives them as strangers, and therefore guests, in accordance with the ancient and still active code of hospitality in effect for peoples of the desert. It is only as the beings begin to speak that Abram perceives them as more than human.

What the angels say in this story is not important yet. That is part of the next aspect of an ESE, which is Revelation. Remember, we are slowing everything down to the foundational elements of the ESE itself and marinating in the story, instead of jumping to conclusions, theologies, dogmas, and interpretations. All we know for now is that there are angels or messengers of the Lord under the tree to visit with Abram and Sarai. This is ‘who is showing up’.

Angels, it should be noted, sometimes take the form of humans, since it is a recognizable appearance which diminishes the element of fear. Angels, generally speaking, are fearsome and terrifying creatures most of the time, which is why they always introduce themselves with an initial statement: “Do not fear!”

This leads us, though, into a brief discussion around what I began this essay with; namely, “What is beauty, and why is something said to be beautiful?” At the beginning of the Renaissance, in the late 1200s and early 1300s, angels began to be depicted with shimmering halos and glistening wings.

The desire at the time was to recapture some of the ancient ideals of the Beautiful and apply those ideals to the things of God. Philosophers of the day, most particularly, St. Thomas Aquinas (@1225-1274), began to apply Greek ideas to the systematic theologies surrounding the Christian faith. Aquinas, who relied upon the Holy Scriptures in conjunction with the recovered philosophies of the ancient world for developing his philosophical thought, discerned from Paul’s letters in the New Testament that God reveals God’s self to us in three primary ways – that which is Good, that which is True, and that which is Beautiful. Aquinas’ recapitulation of Scripture into applicable conceptual ideas provided foundations that transformed thought, science, and art throughout the Western world. It is partially why he is considered THE Doctor of the Church by the Catholic Church.

Aquinas was primarily an Aristotelian, a follower of the Greek philosopher Plato, who was himself a follower of the great Greek philosopher, Socrates. In some areas, however, Aquinas leaned into the Platonic. Plato believed that things, such as they are, gravitate toward a perfect form. As an example, Plato would say that there exists, in a non-material way, a perfect form of a chair. The chairs we create in the material world come closer to or fall away from that perfect form. That which comes closer to the perfect form of a chair is more beautiful as it approaches that perfection; while a chair becomes less beautiful the further it deviates from that perfect form.

Beauty, at least in this functional example, is therefore dependent upon this form and exists as a non-subjective ideal, assuming one is capable of discerning what the perfect form is or is not. Beauty, in this way of thinking, is an objective standard by which all things seek to conform themselves toward. This is, of course, the primary problem with Plato’s conceptions of forms. Who determines the form, or more particularly, who determines who is closer to the form and who is further away? What training exactly does one need to discern such things? The problem complexifies immensely when we deal with artistic expressions.

These questions were also the questions one of Plato’s students kept asking. That student was Aristotle. Aristotle broke from Plato, after almost 20 years as Plato’s disciple, and began to assert that, rather than attaining towards a form, things became what they truly were when they fulfilled the function for which they were created. In this way of thinking, then, a chair is truly a chair when it fulfills the primary function of a chair. There is no ‘perfect form’ of a chair that exists. Instead, there are better ways for a chair to function and less better ways for a chair to function. (I simplify Plato and Aristotle here in an almost criminal way…).

While Aristotle’s views on beauty are sparse, we can extrapolate from the Poetics that beauty has something to do with the function of artistic expression to elicit emotions for the sake of purging them, sometimes called ‘catharsis’. For Aristotelian thinkers, beauty is a kind of epiphenomenon applied to an object in accordance to an object’s ability to fulfill a particular function. It may be that an Aristotelian gave us the phrase “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, since it is an applied, subjective perception of how a thing works relative to its function. For a Platonist, however, beauty is an inherent quality of a perfect thing, or even a fundamental aspect of that form. Beauty exists as a defining element of the universe and therefore cannot be merely a subjective response.

For all practical purposes, I am a Platonist when it comes to beauty. It should be noted that Plato was deeply suspicious of human attempts to attain the beautiful, since it was an exercise in the temporal and material world that elicited emotional and human responses, which were always likely to lead a person away from truth.

But I was talking about things and entities that show up in an ESE, the aspect of Appearance. What does beauty have to do with it all?

When we seek the meaning of an ESE and attempt to integrate the experience into our lives, we make some deep assumptions about the nature of the universe and its construct. Meaning making is an act of making sense of experience and the world that surrounds us. The mere act presumes that there is sense to be made of what has happened to us.

Here, we can break in two ways. First, we can assume the universe has an order to it that is designed, or at least lawful in accordance to scientific laws, to make sense somehow. From this, we can assume that an ordered universe that makes sense wants us to make sense of that universe, which is a very simple way of defining what is sometimes called “The Anthropic Principle”. The Anthropic Principle (AP) accounts for the precision of certain measures of the universe, wherein if even one of the measurements is off by an infinitesimally small amount, life would not exist anywhere. The principle says that, since life does in fact exist, the universe is designed for life to exist. There are different flavors of AP, ranging from weak to strong. In the view of the Strong AP, we are driven to make meaning of things that happen to us because we and the universe are designed to do precisely that.

Second, we can assume that the universe is an historic conglomeration of many chaotic events that lead to specific outcomes. There is no sense to be made because it is not relevant to the chaos of the universe, regardless of its adherence to physical laws. (Chaos does not mean random; it means something like unrepeatable patterns that function within particular laws of physics.) We, as beings who come about because of the controlled chaos of evolution, achieved our status as apex predators because we evolved to perceive repeatable patterns within the chaos that surrounds us. Acting on those patterns layers on the previous patterns that got us to where we are now, and therefore we perceive patterns that ‘make sense’ and we repeat them. Consciousness, then, is a kind of recursive repetition of pattern making within highly intelligent beings, a discrete event woven together to appear always present in our aware lives. We then reverse engineer the patterning to create patterns that please us. In this way, consciousness is an illusion, a trick of the mind reinforcing behavior by forcing us to believe we had some agency in the action we took. This seems like a ridiculous idea until we understand that fMRI and other measures show that the brain generates commands to the body milliseconds prior to our conscious awareness of the movement we think we have decided to make.

Regardless, both options require meaning making in order to function as a being in this world. Both views require a huge commitment of will to accept. Like many ideas, if such things matter to us, we must simply choose, finally, based on our personal experience and knowledge – so that we can make meaning. Even if we did not want to make meaning of what has happened to us, we are driven by the material construct of our brains to do so.

For the purposes of this work, I have come to adopt a view that assumes beauty to be a fundamental aspect of the creative workings of the universe and world. I also assume a higher being, and therefore a higher self that reaches into the spiritual. As a result of these assumptions, I believe we live in what film-maker and podcaster JF Martel calls ‘the aesthetic universe’. By this, I think he means that the arc of the universe always bends towards beauty and the things of the universe orient themselves towards the primary principle of beauty. Aesthetics is simply the word we use for the application of beauty in the creation of material things.

When something or someone shows up in an ESE, the aspect of Appearance, part of how we begin to make meaning of what has shown up depends on how we construct the world we live in. We have some choice in the construct, at least as individuals, and we also need to recognize much is beyond our ability to perceive in terms of cultural, familial, biological, and ideological influence.

There are many philosophical, religious, and sociological/psychological constructs out there by which we can make meaning of the extraordinary. Sometimes, the ESE itself will provide clues to the construct it wishes to be integrated within. In my case, that construct calls for an understanding of the universe as fundamentally constructed on a superstructure of beauty.

What is your construct for understanding what has shown up for you in your extraordinary spiritual experience?

Peace and grace to all!

Dr. Seth Jones